Censor (2021) | Review

Although it’s hard to imagine now, with every other show streaming blood and gore while spewing f-bombs punctuated by soft-core porn, it was a different story in the 1980s. We had the PMRC censoring rock and rap records for explicit language, folks brandishing bibles against the scourge of Satanism, and theaters banning certain horror films, relegating them to the underground “video nasty” rental circuit. Ah, the good old days!

1980s-born Welsh writer-director Prano Bailey-Bond certainly has a soft spot for this era of repression—Censor is her first feature, but back in 2015, she produced a short film with similar themes called Nasty—and she exploits it beautifully, with great command of the cinematic language.

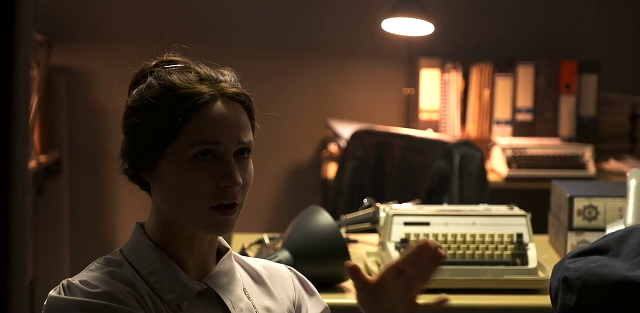

Niamh Algar plays Enid, a prim, straightlaced censor working for Britain’s Film Classification Board. We meet her in a dark screening room as she views a particularly gruesome B-grade horror flick and takes notes. “Eye gouging must go!” she writes, going about her workday routine. The decapitation is okay because it’s over-the-top, but the eye-gouging will be cut, she later explains to her boss.

Usually, her job is just a slog, but things take a turn when a copycat killer murders his family in the same fashion and one of the films Enid passed. When her name is released to the press in connection with the crime, paparazzi and anonymous phone calls chip away at her peace of mind. Still, she soldiers on, even through a particularly gruesome slasher called Don’t Go in the Church. It’s the latest movie by an underground horror director named Frederick North (Adrian Schiller) and, to Enid’s own horror, the star of the film resembles her missing and presumed dead sister, Nina.

Censor then takes us on a deep dive into Enid’s long-buried shame and guilt, which has now been triggered to resurface. Nina vanished decades ago while the sisters were out playing in the woods, and Enid has never been able to forgive herself. She is convinced that Nina is still alive and out there, somewhere… maybe even starring in schlock horror films. Enid decides to pay a visit to the reclusive, enigmatic director of Don’t Go in the Church, but he doesn’t have the answers she’s looking for—worse, he turns out to be just the kind of perv who make such nasty films.

The mystery is intriguing, but it’s the look and feel that really sells the bill of goods. Visually similar to great throwback horrors such as The Editor (2014) and Berberian Sound Studio (2012), Censor splices together an eerie landscape of sound design, a John Carpenter-inspired score, and charmingly scratchy strips of “film.” There’s subtle surrealism to Enid’s undoing that may remind you a bit of Possession (1981) or In Fabric (2019), but ultimately, Censor cuts deep into its own unique world. The filmmakers cleverly switch to the square VHS format from time to time, and the costuming is spot-on without going quite as crazy with the shoulder pads and animal prints as hapless fashion victims really did back then.

Enid is an unreliable narrator, making us wonder whether we’re watching a movie in her paranoid, grief-stricken mind or if we’re witnessing actual brutal killings that veer into David Cronenberg territory (with a touch of Tobe Hooper). As you may have noticed, all the directors I’ve referenced are male—so the fact that a woman co-wrote and directed Censor makes it that much more delightful.

I say “delightful,” but unlike, say, The Editor or Crystal Eyes (2017), Censor is not a comedy/horror hybrid. It’s a gritty, absorbing, and often gory, horror/suspense film that takes a hard look and who’s watching and what it all means.

Having heaped all that praise—and yes, Censor is one of the best horror films I’ve seen so far this year—its conclusion felt a bit rushed and incomplete.