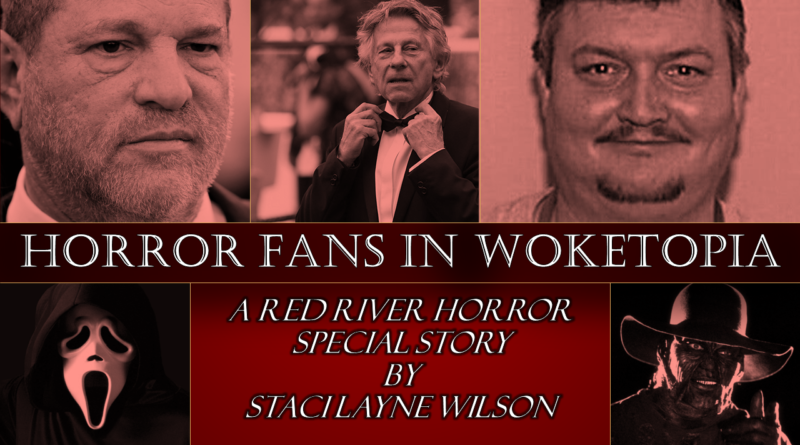

Horror Fans in Woketopia | how we cope

If you’re of a certain age, you probably remember watching The Birds without a thought in your mind about director Alfred Hitchock’s alleged unwanted sexual advances toward lead actress Tippi Hedren. Or maybe you knew about Roman Polanski’s mid-1970s conviction for the statutory rape of a 13-year-old aspiring model, but you could watch Rosemary’s Baby and enjoy it, and no one would rake you over the coals for it.

What if you’re an Asia Argento fan? Should you watch her movies in the wake of the recent scandal involving the young actor who played her son in The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things (which she also directed)? After all, we were warned: she is quoted as saying, “What you might see as depravity is, to me, just another aspect of the human condition.” Should artists get a pass for their depraved acts if their art is really, really good?

And what about retroactive wrath? Once the maker of the movie is dead and buried, do his or her misdeeds evaporate or does their name taint the product forever?

There are no easy answers to such complex and evolving issues, but the debate is worth exploring—especially for us as horror fans, since our beloved genre is, by its very nature, often misunderstood.

We rounded up four erudite pundits…

- Miranda Bailey, filmmaker and founder of CherryPicks

- Patrick Lee, former news editor at NBCUniversal’s SCI FI Wire

- Linda Rose, screenwriter and Hollywood historian

- Brian Wallinger, critic at The Movie Revue

…and asked them some thought-provoking questions.

It seems a lot of horror fans practice “selective outrage” – for instance, they may furiously condemn sexist or racist behavior in movie producers, directors, and actors, yet they blithely post gangsta rap or 80s metal videos on their social media timelines. Music by those artists probably reflects their real lives, so… Isn’t that contradictory?

Miranda Bailey: Yes and no. With the invention of social media, all of us have the ability to look backwards in our lives for a lesson in hypocrisy. What I’ve noticed is the way we seem to judge what was said or what happened during other time periods as if it were made today. It’s 2019; we have new eyes, new ideals, and most importantly: new boundaries. With any form of art, it becomes particularly tricky when we want to condemn it and why. The mob mentality we participate in can bring someone’s career to a screeching halt from a tweet they did 10 years ago—when the same ideals, rules, and boundaries didn’t exist. We are now held accountable for rules that are put in place in the future and I’m not sure that makes too much sense other than it is a starting point of what we currently find as acceptable values.

The mob mentality we participate in can bring someone’s career to a screeching halt from a tweet they did 10 years ago—when the same ideals, rules, and boundaries didn’t exist. | Miranda Bailey

Patrick Lee: I don’t think so. In the first case, one is criticizing behavior that affects people in the real world and causes real harm to people who had no choice in the matter. In the second, one is showing a preference for artistic expressions that may be offensive or problematic, but that are nevertheless art that doesn’t directly affect people. One could argue whether art affects the attitudes, feelings or inclinations of people, but there is no established causal relationship between artistic expressions and behavior, at least not in the scientific literature that I’m aware of. Does some music or videos offend people or trigger them? Yes. But should they be censored because of that? I’d argue no (unless they break laws that prohibit specific kinds of expression, which exist, as does a mountain of case law about what can and cannot be censored). And if you don’t censor them, then you can’t tell people they can’t like them just because they may offend others who are otherwise in no position to subject themselves to such artistic expressions if they choose not to.

Linda Rose: It is very contradictory. If you are outraged at sexist and racist behavior, then it should be across the board outrage regardless of the industry. Unfortunately, people sometimes don’t want to believe that celebrities/stars/genius-talented people can do wrong. Recently I met a girl who loves Michael Jackson and she said to me, “I love MJ and won’t hear a bad word said about him.” When I commented on a Facebook post [of hers] about all the good things Jackson has done, I commented that he has done appalling things also. So, she unfriended me. If people really love a celebrity, they forget that these people are human and fallible and then want to stick their head in the sand when they find out the person has perpetrated awful or shocking behaviour. I guess it’s because they have a certain image built up in their mind about this person and can’t cope with the psychological implications of what they thought about that person, isn’t necessarily true.

Brian Wallinger: In retrospect, newer generations of cinephiles are becoming enraged by the social climates of dated films. For example, the slasher genre, a theme inspired by the Giallo films of Italy popular in the mid 1960s-1970s, often involved young women being objectified in a sexual manner and then abruptly murdered in a graphic way; usually by a man. I mean it’s all about a sort-of reflecting perspective, like who you are as an individual it is possible to enjoy these films for their campiness and not endorse (in real life) the tones and themes that are the fundamental elements of these pictures. It is of course possible to find an appreciative balance through it all, [but] it can be problematic given the climate we find ourselves in now. Especially with the Twitter community amongst other various social media sites and overwhelming toxicity that exists in those forums.

So many of the Dimension horror films have Harvey Weinstein (consensus: awful) attached to them; but also, Wes Craven (consensus: awesome)—does our love of Wes supersede our hatred of Harvey? Is it okay if it does?

Bailey: I think the majority of consumers outside of the bubble of Hollywood don’t really care what those filmmakers did or do that is not meeting today’s standards of acceptable behavior. They only care if the movie is good or not.

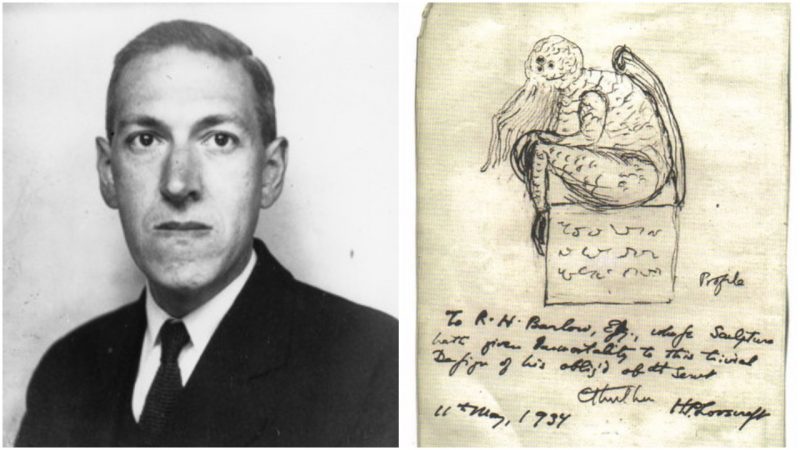

Lee: This is a complicated issue. How do we reconcile our consumption of art produced by people who have done terrible things? I think every person has to make peace with it on their own terms. I don’t know if there is a right answer or wrong answer, and I think different people of good faith could come to quite different approaches to the issue. I approach it with this guideline: Will my consumption of this particular work of art directly benefit a person who is still around and able to continue doing terrible things? If the answer is no, I have an easier time indulging in it. Take the stories of H.P. Lovecraft. He was a racist and awful person. But he’s long dead. My purchase of a book of his stories does nothing to further his bad behavior. But take Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card. He is alive and continues to be a homophobe and religious fundamentalist with loathsome views. If I buy a ticket to see the movie made from his book, I directly benefit his career and enable him to continue doing things that I believe harm people. In the case of Harvey Weinstein: If I buy a Blu-ray of Scream, does that benefit Harvey, who is still alive and still a loathsome human being? If the answer is yes, then I’d have a problem with it. But if his business ties with Dimension are such that he no longer benefits financially, then I’m okay with it.

Rose: We cannot go back into the past. The movies have already been made and therefore we should still enjoy them. Unfortunately, but maybe also fortunately, every time we see the Weinstein logo at the beginning of a movie, it will remind us that Harvey was a really bad guy and remind us that the behavior he perpetrated is not acceptable. We also have to remember a movie is not made by one person. A movie is made by a group of talented people. And we can’t stick a whole group of talented people in the same bucket as one awful person.

Wallinger: When Harvey had started out, he had no money. He was flat broke looking for a break and through the means of an easily accessible product. His first produced film, The Burning, was released in 1980 on a very modest budget (also, it has some of the most stunning practical effects, which were created by Tom Savini). The Burning is a standalone shlock film that overall is engaging above the rest of the trash surrounding that moment in time. After Halloween, many horror films replicated the themes and atmosphere ten times the world over and a lot of people made a lot of money. This would ultimately put Harvey on the map with [his company] Miramax and an array of films, along with probably the best thing out of this deal: Quentin Tarantino. However, it isn’t a secret that Harvey was/is a sexual predator that used his power to influence and abuse many women that only now the true nature of him as a person and the damage he has done is being noticed and given appropriate action. Though Harvey is not the only one. Roman Polanski, Kevin Spacey, Bryan Singer; and so on. The concept of separating the art from the artist is something I believe is a crucial yet divided notion that has created quite a bit of debate and controversy amongst not only fans, but critics and other filmmakers as well. In my opinion, it is possible to love a film regardless of these things but it is possible to always remember so that we do not let these things continue to happen.

Can we openly enjoy good horror movies made by bad guys? Rosemary’s Baby, for example… can we like that movie because it was made before his statutory rape charge, and then not watch everything he did after 1977?

Bailey: It is likely actual movie fans don’t really care what the artist did outside of the work itself. But the people that make the art, the producers and financiers who make the movies do care. So, it’s up to us to change whose artistic voice we support. That said, it’s hard because sometimes you find out after that you supported someone who’s broken today’s social or ethical rules.

Lee: Roman Polanski is still around and still benefiting from residuals from his films, I presume. The more we know about what he’s done, the less we should be inclined to indulge in his work until he’s no longer in a position to benefit. As for whether we should judge people by “today’s standards,” well, yes, we should. Today’s standards are the result of our coming to terms with the injustices of the past. Now that we recognize them, we can no longer excuse them even if they occurred 30 years ago, or 40 or 50. There were, after all, people who were around at that time who didn’t do the things Hitchcock or Polanski did, and they didn’t because they knew they were wrong then just as we know they are wrong now. So why should people who got a pass then get a pass now? Since Hitchcock is dead, though, I see no problem appreciating his work on its own terms, while keeping our eyes open about how the films were made and how the man treated the people he worked with. It’s all part of history now, and the people inform the art, and it’s okay to know all of it and weigh it and come to judgments about it.

Rose: Bad guys can be talented too. The movie, as a product, is separate from the person/s who made it. Would we stop drinking Coca Cola if we found out the president of the company was a pedophile? I don’t think so.

Should there be a statute of limitations for bad behavior? After all, it’s really not logical to hold people from the past to today’s standards… or is it? Hitchcock is a well-known perv who made some of the famous “Hitchcock” blondes feel really uncomfortable. But that was so long ago. Is it okay to still celebrate the director for his cinematic genius?

Bailey: In my opinion yes. Though that’s not a popular opinion. But I’m also a filmmaker. I watch their films and their work and I learn from it. As a form of art and tool for teaching art it is important to see their work if it’s valuable and was considered auteur during that time period. But I also think it’s valuable to understand the history of those individuals so we don’t repeat it.

It is not logical to hold people of the past to today’s standards. | Linda Rose

Rose: I really do think it is not logical to hold people of the past to today’s standards. They lived in a completely different world to what we do now. While Hitchcock (as far as we know) did not have a casting couch, it is well known that the big producers and film companies have had the casting couch since the invention of cinema, and the majority of actors would have some experience with this. We live in a patriarchal society, where white men run everything and while this is slowly changing, to be factual, that’s how things were in the past. So, as far as Hitchcock goes, yes, it is okay to celebrate his cinematic genius. Jack Warner was well known to use the casting couch – are we never going to watch a Warner Bros. movie ever again or enjoy them? Or refuse to celebrate the great actors and movie makers of those days? Of course not.

Many horror fans refuse to watch anything made by Victor Salva (Powder, Jeepers Creepers franchise) because he molested an underage boy. But Salva stood trial, was convicted, and served his time. To our knowledge, he has not repeated the offense. But that’s not good enough for many people. Is there any point at which someone can be forgiven?

Bailey: I think forgiveness is always something we should strive for. But it’s hard when it comes to the mistreatment of children. I personally won’t watch those movies, but to be honest, I think Jeepers Creepers is crap. So perhaps he isn’t a person for me to reflect on for this specific question.

Lee: Again, it’s a complicated issue, and different people of good faith can reach differing conclusions about whether they will indulge in Salva’s art or not, and both will be right. I do believe we can forgive people if they have accepted responsibility for their bad behavior, and paid appropriate penance, and, especially, have made amends to their victims and resolved not to transgress again. But I can also see the point of view of someone who believes that is never enough when it comes to certain transgressions, such as child abuse. I don’t know that much about Salva’s current situation to know whether I’d pay to see one of his films (or, were I a producer, if I’d be willing to hire him). I’d have to know more to make an informed decision. I think we can decide such things on a case by case basis.

Rose: This is a difficult one. I think that if there is a one-off incident and the person is punished, we should give them some kudos and not keep punishing them for one mistake. It is a different story however if the person continues with same appalling behaviour time and time again.

Do you agree or disagree with the following: Certain great horror movies have risen above their ties to the people who made them and they now belong to the audience.

Bailey: I would need specifics in terms of person and project to really answer this question. So, I guess then the answer is… it depends on their body of work, it depends on what they are accused of, it depends on what the standards of morality was during their time. For instance, child molestation or rape has never been acceptable! Yet, sexism, racism, ageism, body shape shaming or disability shaming, have all had a time and place where most audiences didn’t think it crossed the boundaries, but perhaps that it pushed up against the boundaries. And often this was exactly what the audiences liked about certain artists. That has changed today. I’m glad it’s changing and I think we can still find ways to push the boundaries without bringing others down and without harming humanity.

I believe all art separates from its creator once it is complete. | Patrick Lee

Lee: Speaking from the point of view of a critic considering a work of art, I believe all art separates from its creator once it is complete. I believe the critic’s job is twofold: To discuss the work of art on its own terms, and to place that work of art in the context of its creation, which necessarily includes an honest and cold-blooded assessment of its creator. Do works of art such as horror movies eventually belong more to the audience? I don’t think audiences own a work of art any more than I believe an artist does once it’s in a movie theater or hanging on a museum wall. It lives and exists outside of such considerations. I believe an audience owns its reactions to that work of art, and an audience member can comment and critique it to her heart’s content, and own that as well. And I believe an audience member can love a horror movie, and that’s a beautiful and desirable thing: That relationship is real and belongs to the audience member. But an audience member has no more of a claim to a horror movie than a visitor to the Louvre has a claim to the Mona Lisa: It “belongs” to culture, to history, to the ongoing legacy of humanity. Audiences come and go, but art, hopefully, is eternal. Do the plays of Euripides belong to the ancient Athenians? Euripides is long gone. The Athenians are long gone. The plays live on, and they’re what matter.

Rose: Movies like Psycho, Halloween, The Exorcist, Final Destination and Friday the 13th, and many others have made a big impact on people and are still enjoyed today by movie watching audiences. And some are so good they have developed their own franchise. But I bet if you asked the cinema watching fans, who made these movies, they wouldn’t have a clue.

How do you choose where to draw the line for yourself?

Bailey: The line is moving every day. I just try to be true to myself and my own values.

Rose: I think we do have to draw the line where we have our “icons” who, while being very talented and also powerful in the industry, use that talent and power to prey on others. In our current climate the general public should be more aware that what you see on TV or the cinema screen is fiction and that in real life the people we adore and idolise are human and have faults. And some of these extremely talented people, for example: Bill Cosby, R Kelly, Michael Jackson, Harvey Weinstein to name a few, no matter how talented or genius they are, are actually really awful people. Therefore, they forfeit their right, no matter how talented, to be in this or any other industry, especially when they are leaving a massive wreck of damaged human beings in their wake. With the advent of social media, we are more able to scrutinise our “idols” and what they are doing in their public and personal lives. And we should be choosing those who use their talents for the good of humanity, and boycott those who are predators – no matter if they are a genius in the cinema, music or TV industry.

Our society is much more terrifying to me than any movie. | Brian Wallinger

Wallinger: Being a critic, and a filmmaker coming off of my fourth full-length movie, it is oftentimes complicated to draw “lines.” As an artist, given the circumstances, my goal is to cross lines. And that may sound rather pretentious; to fully understand what I mean, it’s going after the senses, making audiences feel not only entertained but provoked into thinking past the limits of their comfort zone. And with a genre like horror (I have never made a horror film), the response tends to be laughter and I think that is a way of hiding our true feeling of fear, no one wants to admit that a simple story about a guy in a mask stalking a woman scared them, but it did. A lot of films have, and continue to do so, despite their age. Our society is much more terrifying to me than any movie, but as a filmmaker, I’d want at least to be able to create a kind of film that gives in to the notion of our current climate of just everything and anything. The occasional horror film does achieve this, and when it happens, it’s significant, because a work of fiction that embraces the ideology of real life and reshapes it into a work of art that haunts us and consumes us is a rare thing.

To sum up the ever-growing gulf between fans on different sides of the fence, Wallinger posits: “No one is erasing anything. Things lose popularity because they don’t stand the test of time. [But some people] too quickly dispense with nuance, context, and the possibility anyone’s experienced personal growth without their browbeating them into lumps of shame. Being pro-social justice is awesome. Being a social justice warrior is dangerous. Warriors belong in wars, and wars hurt everyone and everything in its path; especially when we’re already trying to survive in this extremity-driven outrage culture. Being well-intentioned isn’t enough.”

What do you think? Weigh in by commenting below.